Coaching in Context:

Bringing Organizational Culture into Coaching Engagements

By Daniel Denison (Denison Chairman & Partner)

and Bryan Adkins (Denison CEO & Partner)

Bringing Organizational Culture into Coaching Engagements

and Bryan Adkins (Denison CEO & Partner)

Coaching in Context

Finding the right connection between organizational contexts and leadership competencies in coaching engagements can be difficult. Competencies are assumed to be a characteristic of the individual, and the purpose of the engagement is to improve the effective deployment of those competencies. Context is often de-emphasized, especially when the focus of the coaching engagement is on the psychological or behavioral skills of the executive. Even when context is included in the discussion, the primary sources of “data” about that context are often limited to the executive’s perception of the context, as that perspective emerges during the coaching session itself. Experienced coaches often complement their work with broader input from key stakeholders, but a clear sense of the broader organizational context can be hard to come by.

We start by first presenting a case study from one of our clients, illustrating our approach to coaching in context, and the insights that it provided for aligning leadership development and organizational change. We then go on to present a framework showing how the organizational context in which a leader is working can dramatically influence the key priorities in a coaching engagement.

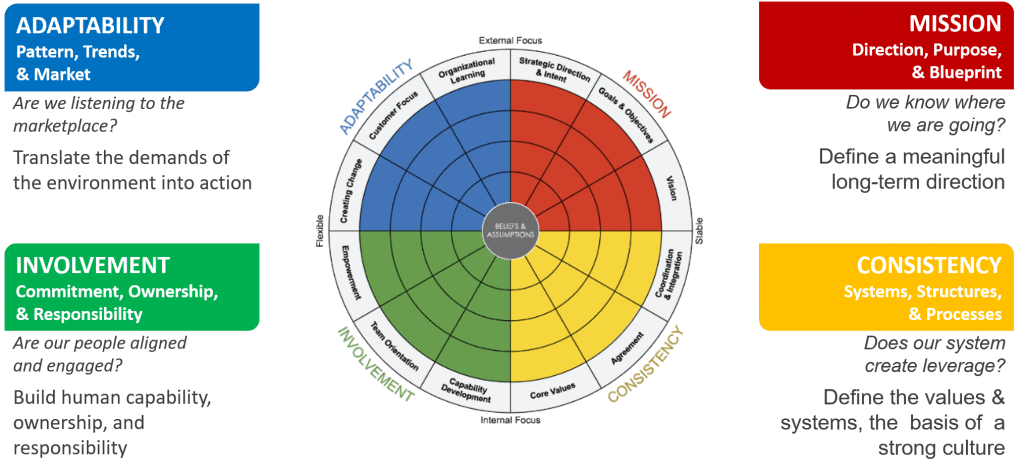

Aligning Around Our Organizational Culture Model

Our approach is enabled by using a common model for assessing both leadership competencies and organizational contexts. For this, we build on our organizational culture model (see Figure 1 below) which serves as a basis for both our organizational culture assessment and for our leadership development assessment (Denison & Neale, 1996; Denison, Hooijberg, Lane, & Leif, 2012; Denison, Nieminen, & Kotrba, 2014). Both of these assessments are based on the common model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the Model

This model focuses on managerial behavior and values and was developed from research on four cultural traits—involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission—which predict aspects of business performance such as profitability, growth, and customer satisfaction (Sackmann, 2011; Denison, Nieminen, & Kotrba, 2014). At the organizational level, these four traits are measured through a set of 12 indexes that are benchmarked against a global sample of firms. At the leadership level, the four traits are measured through a set of 12

indexes that ask a parallel set of questions about leadership behaviors. The model is supported by extensive research and a long-standing focus on business performance, including a recent time-series study which helps address the direction of causality in the culture and performance studies (Boyce, Nieminen, Gillespie, Ryan, and Denison, 2015; Denison, Hooijberg, Lane, & Leif, 2012). Here are the four core traits:

Mission. Successful organizations have a clear sense of purpose and direction that allows them to define organizational goals and strategies and to create a compelling vision of the organization’s future. While leaders play a critical role in defining the mission, it can only be reached if it is well understood, top to bottom. A clear mission provides purpose and meaning by defining a compelling social role and a set of goals for the organization. We measure three aspects of mission: strategic direction and intent, goals and objectives, and vision.

Adaptability. A strong sense of purpose and direction must be complemented by a high degree of flexibility and responsiveness to the business environment. Organizations with a strong sense of purpose and direction can often be the least adaptive and the most difficult to change. Adaptable organizations, in contrast, quickly translate the demands of the organizational environment into action. We measure three dimensions of adaptability: creating change, customer focus, and organizational learning.

Involvement. Effective organizations empower and engage their people, build their organization around teams, and develop human capability at all levels. Organizational members are highly committed to their work and feel a strong sense of engagement and ownership. People at all levels feel that they have input into the decisions that affect their work and feel that their work is directly connected to the goals of the organization. We measure three characteristics of involvement: empowerment, team orientation, and capability development.

Consistency. Organizations are most effective when their values and actions are consistent and well-integrated. Behavior must be rooted in a set of core values, and people must be skilled at putting these values into action by reaching agreement that incorporates diverse points of view. These organizations have highly committed employees, a distinct method of doing business, a tendency to promote from within, and a clear set of do’s and don’ts. This type of consistency is a powerful source of stability and internal integration. We measure three consistency factors: core values, agreement, and coordination and integration.

Like many contemporary models of leadership and organizational effectiveness, this model focuses on a set of dynamic contradictions or tensions that must be managed. As Schein and others have noted, effective cultures always need to solve two problems at the same time: external adaptation and internal integration. Thus, four tensions are highlighted by the model: the trade-off between stability and flexibility and the trade-off between internal and external focus. In addition, the diagonal tensions between internal consistency and external adaptability, and “top-down” versus “bottom-up” tension between mission and involvement, exemplify some of the competing demands that organizations face.

For each of these dynamic contradictions, it is relatively easy to do one or the other, but much more difficult to do both. Organizations that are market-focused and aggressive in pursuing every opportunity often have the most trouble with internal integration. Organizations that are extremely well-integrated and controlled often have the hardest time focusing on the customer. Organizations with the most powerful top-down vision often find it difficult to focus on the bottom-up dynamics needed to implement that vision. Effective organizations, however, find a way to resolve these dynamic contradictions without relying on a simple trade-off.

At the core of this model, we find underlying beliefs and assumptions. Although these deeper levels of organizational culture are difficult to measure, they provide the foundation from which behavior and action spring. Basic beliefs and assumptions about the organization and its people, the customer, the marketplace and the industry, and the basic value proposition of the firm create a tightly-knit logic that holds the

organization together. But when organizations are facing change or encountering new challenges from the competition, this core set of beliefs and assumptions, and the strategies and structures that are built on this foundation, come under stress. When that happens, the organizational system and the culture that holds it together need to be reexamined.

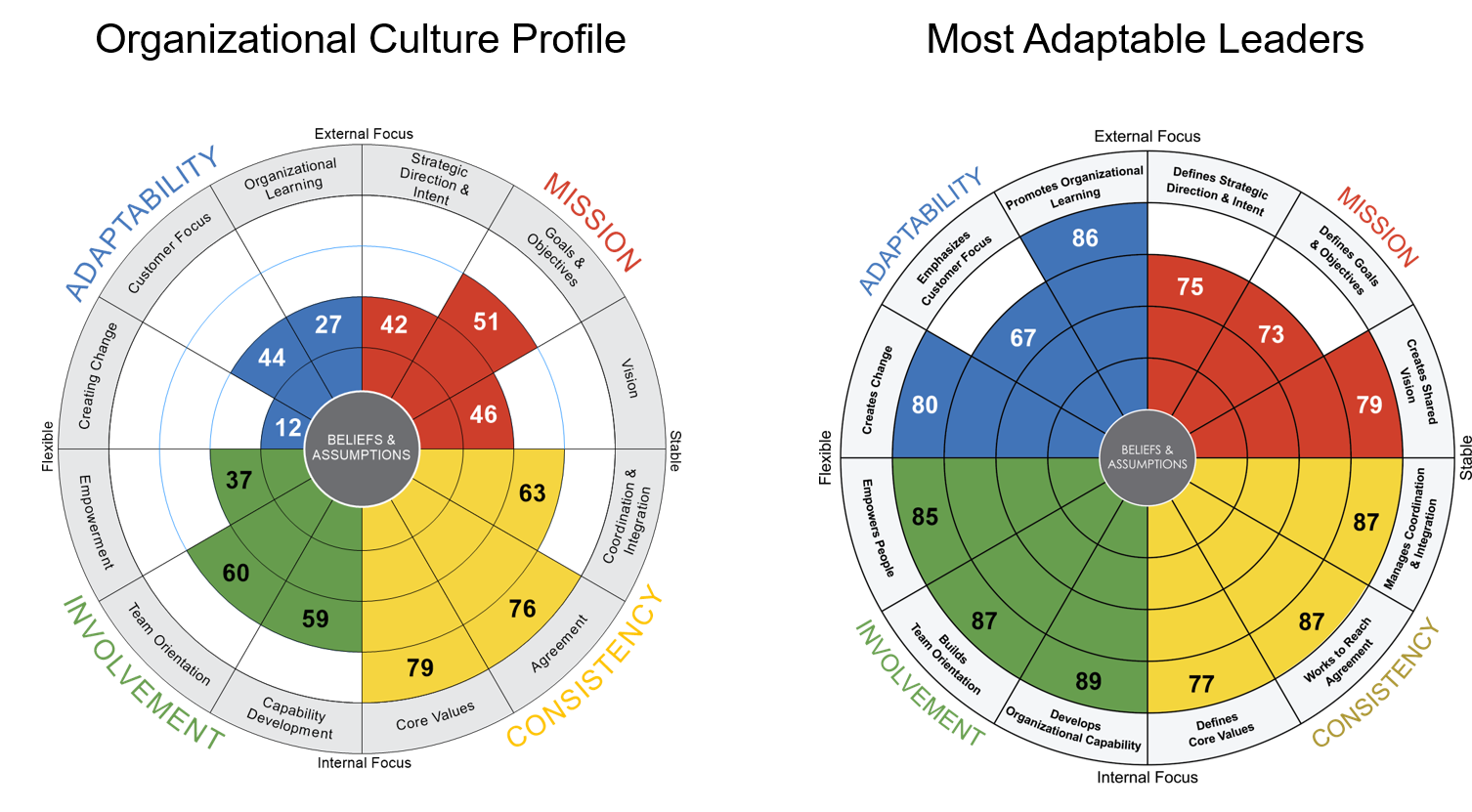

A Compelling Case Study

This case study comes from our work with a large global client in the energy sector. Our work with this firm included both the assessment of the cultures of many different sub-units of the organization and the 360 assessment and coaching of many different leaders throughout the organization. As our work evolved, it became clear that the agenda for the change-focused organizational culture work and the development-focused leadership coaching work converged in an interesting way. For example, at the organizational level, the firm was increasingly concerned with its lack of agility. This issue often emerged in the individual coaching sessions with the executives. But it also became clear that there were a large number of executives who did show a high level of adaptability, as judged by their direct reports, peers, and bosses.

When we began to look at these results more systematically, an interesting pattern appeared. The overall culture profile clearly showed the organization’s limitations in areas of adaptability, and especially in the area of creating change. But when we looked at the leadership 360 composite for those leaders who scored above average in adaptability, it quickly became clear that this organization definitely had the leadership talent needed to become more agile.

Figure 2. Coaching Leaders in Context

We recommended that the firm mobilize this group of leaders to help define the changes that would generate greater agility in the firm. These leaders were a cohort that actually felt that the organization was holding them back, and that had the extensive experience and credibility to contribute to the change process. Awareness of this contrast between the leader’s data and the culture data for their part of the company became a useful asset in our coaching sessions.

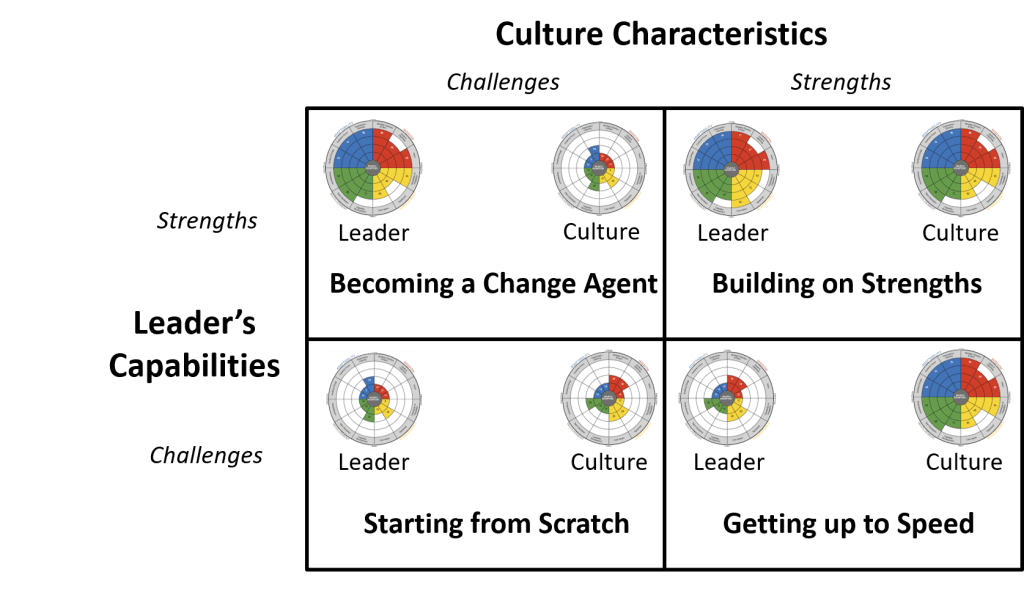

Coaching in Context: A Useful Framework

This insight led us to develop a framework for viewing leadership results in the organizational context to help improve the coaching process. This framework builds on our earlier research and the experience that we’ve gained through our practice (Nieminen, Biermeier-Hansen, & Denison, 2013). The framework contrasts the strengths and challenges of the individual leader against the strengths and challenges of the organizational culture. This allows us to define four major categories for coaching in context. “Starting from Scratch,” “Getting up to Speed,” “Becoming a Change Agent,” and “Building on Strengths.”

Figure 3. A Framework for Coaching Leaders in Context

Starting From Scratch. When a leader has real limitations in an area where the organization also has significant challenges, this makes for a difficult coaching challenge. There are few role models and helpful mentors in the organization, and the individual leader is starting from the beginning. This means that the coach’s most important contribution may come from their ability to import outside resources or expertise to help define the next steps. Support for the leader’s development within the organization may also be quite limited. “Why do we need that?” may be a common response. But with a clear picture of the limited support for development that may exist within the leader’s environment, a talented coach may be able to help build the case for identifying other forms of support.

As an example, consider the coaching work we did with Katie Chan,

who took on the CHRO role of a tech company in Silicon Valley. Katie’s background was in Compensation and she was doing well until her firm acquired a competitor and she was chosen to lead the integration team! Then she struggled. Her 360 results showed that she was not doing very well in her role. But the culture results also showed that her organization did not have much experience or expertise in this area. So, her challenge at this point was leading a strategic change in an organization that didn’t have much experience in managing strategic change. Her coach helped her the most when he provided her with outside examples, in her own industry and even introduced Katie to several of her peers in the Bay Area who had successfully made the transition to a strategic HR role.

Getting up to Speed. When a leader’s limitations occur in an environment in which the organization has significant strengths, the dynamic is entirely different. Initially, these results may be quite a bit more intimidating and the leader may feel like they are “on the spot,” and that they need to improve dramatically to fit in and be accepted. But the upside of this situation is that the leader is in a setting where there are rich resources and examples to draw on. Opportunities for role models and mentors are rich, and there are many opportunities. In this situation, the coach does not need to import expertise into the leader’s environment – it is already there. The coach just needs to build awareness of the context and how the individual can connect with internal stakeholders who can help them build an agenda for their development.

Henry Nelson was a talented individual contributor in a Key Account role in financial technology firm in New York. Henry had recently been promoted as the new leader of his team and had been asked to take on a more strategic role. This new role required Henry to provide vision and strategic direction for the team that he had been a member of just months before! He was not well-prepared for this role. But the culture results for the firm showed that his company had a very strong sense of strategic direction, and this made both Henry and his coach aware of the abundant resources that were available to support Henry as he learned these new skills. A key part of the coaching engagement involved connecting Henry with several senior leaders who mentored him well and supported the development of these strategic skills.

Becoming a Change Agent. This situation is more closely aligned with the general pattern outlined in our earlier case study, described in Figure 1. The leader actually has extensive skills in an area where the organization is quite limited. While at first blush this may appear to be a situation in which the individual is just defined as “high potential” because they possess skills important to the organization. It is actually also a great opportunity to try to leverage the individual’s skills to try to improve the organization. In this situation, a coach’s knowledge of the organization’s agenda for change and improvement becomes critically important. Opportunities to leverage a leader’s strengths by connecting them to important activities designed to improve the organization may also have a positive impact beyond just gaining visibility for the leader’s talents and experience in applying them.

Lisa Billington was an experienced line business leader who was promoted into the Finance function in the global energy company that

we featured in our example in Figure 2. Their goal as an organization was to become more agile. And the line management experience that Lisa brought into the function had helped her to lead a number of successful projects designed to make the function more responsive to the needs of the line business leaders. This showed through clearly in her excellent 360 results! But there was one problem. The feedback that Lisa received from her boss was not very good. His perception was that she was pushing too hard and not working very well with her mostly male peers and direct reports. But when the coach asked the boss to consider the culture results that described the context that Lisa was working in, he slowly began to accept Lisa’s tremendous value as a change agent in an organization that needed to become much more adaptable. He also became much more committed to helping her manage the friction that some of her innovative ideas had caused with the group.

Building on Strengths. The final category focuses on situations where the individual leader has strengths that are well established in the organization. The leader’s strengths are a good fit with the organization and there are many opportunities to collaborate with others who share these same strengths, as well as a rich set of resources for continuing to learn and develop in these areas. The coach may have a challenge explaining that the positive skill set that the leader possesses is not very unique, thus unlikely to provide a solid base for a competitive advantage in their career. However, the coach may be able to help the leader build a strategy to define their unique contributions – with the solid foundation of knowledge that they share a critical set of skills with the rest of the team.

Leo Peng had done so well as a technical leader that about a year beforehand, he had been promoted to a strategic role in a large consumer products company in Qingdao. He learned fast in his new role and his 360 feedback showed the results of his progress. His success in his new role had put him in the company of a very dynamic group of peers who were also successful in an organization that was doing very well. The coach’s insights about the strengths in Leo’s capabilities and the strengths in the organization led to a series of discussions about focusing on “raising the bar” for the next step of Leo’s development. This meant that a key part of Leo’s action plans was to engage with the other leaders who were in strategic roles to plan for the next stage of evolution in the strategy function is his business division. Both Leo and his peers were operating at a very high level already, but this coaching engagement helped generate a plan for moving the group to the next level.

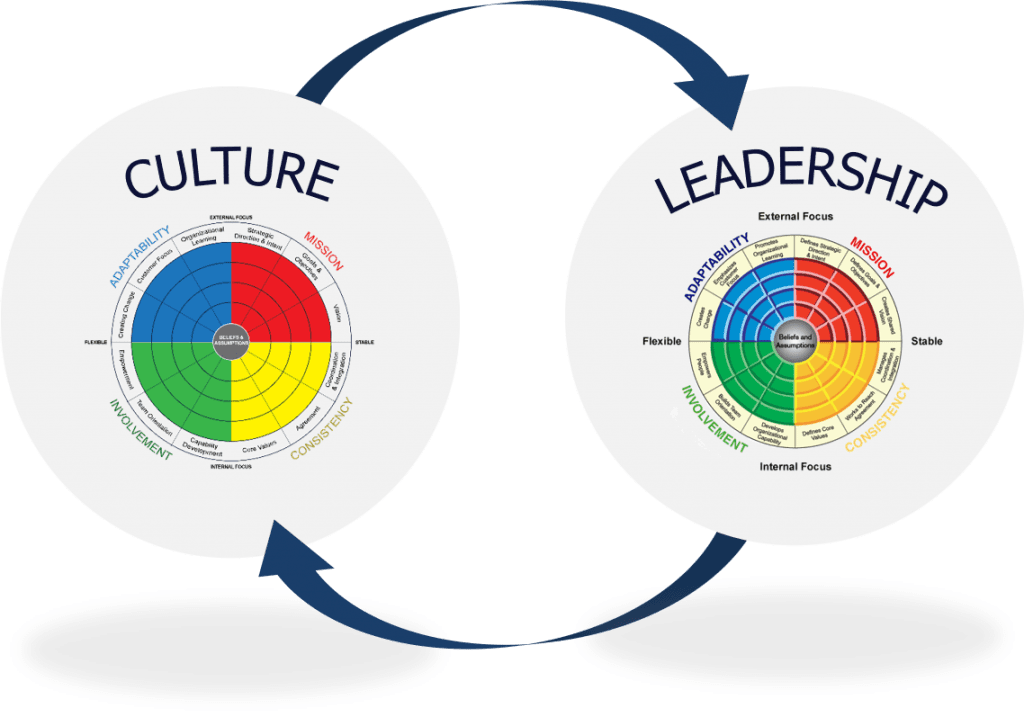

Discussion: What Goes Around Comes Around

As culture guru Edgar Schein once said, “culture and leadership are two sides of the same coin.” (Schein, 1985) So, we must always be aware of the need to deal with both at the same time. Over the short-term, the culture of an organization has a strong influence on the behavior of individuals within it, and the individual needs to concentrate on how to fit into the context in order to be accepted and to perform well. But over the longer term, the people make the place (Schneider, 1987) – the culture is created by the individual members, and especially by the leaders (Denison, 1996). So, leadership development and organizational change must be closely linked, so that leaders are always being developed in a way that anticipates the future vision of the organization’s culture. Otherwise, as the change gathers force, it is in danger of faltering, because the leaders have all been developed to fit well with the organization’s past, not it’s future.

Figure 4. Two Sides of the Same Coin

Many organizations complicate this situation by keeping these leadership and organizational development activities quite separate. The talent agenda is not well-integrated with the change agenda and, in some cases, these two activities are even in competition for resources and attention. The more powerful approach is to integrate them directly, then align the two activities so that they are complementary. This helps to generate a future-oriented perspective for both activities that helps maximize this long-term investment.

Experienced executive coaches around the world, understand this dynamic intuitively, and use these insights as an essential part of their practice. But a more systematic approach to coaching in context can also help to generate greater leverage by integrating these two activities in a more mutually supportive way.