The UofM Cardiology Fellowship Training Program: Building a “Culture of Builders”

by Levi Nieminen, Ph.D., Director of Research & Senior Consultant

According to the New York Times, the number of Americans in the “Gig Economy” grew by 9.4 million between 2005 and 2015.(1) This raises interesting new questions about the meaning of organizational culture.

A gig economy organization has an employee lifecycle that is on steroids. How do you create and maintain a culture in an organization where employees may not even see themselves as members of the organization, and where “membership,” even when perceived as such, is fluid, short-term, or intermittent? How do you reach out to these quasi-members and ask them to play a central role in forming and sustaining the organization’s culture? Further, how do you address the challenge of these individuals being in competition with each other? What roles are needed from the part-timers, short-timers, and consumer-employees in this new organizational paradigm? In short, how do you build connectedness in a fluid organization?

THE UNIVERSITY’S CHALLENGE: CREATING A “CULTURE OF BUILDERS”

These were the issues faced by the University of Michigan Cardiology Fellowship Training Program. But what was there to improve? The program was already among the top tier of programs in a very competitive subspecialty of medicine. “Most programs operate on an old apprentice model, a cottage industry in the post-industrial world,” explains Program Director Dr. Peter Hagan.

“We don’t apply modern, validated, education principles. So, how we train people is not a whole lot different than how people were being trained decades ago. I had this gnawing sense that there has to be a better way than the way we’re doing it right now.” The training model, Hagan realized, had not been adjusted to adapt to global changes affecting every aspect of not just medicine, but modern life. “Like everybody in the business world knows, the world is changing around us. We’ve had an explosion of knowledge and technology. The learners are changing. Society’s needs are changing. And we have a culture problem.” Hagan set out to transform the Program to create what he calls a “culture of builders.” “We want to be the ideal training program. We want to empower and leverage our Fellows to be builders. We want to develop a strong culture, a culture of ideas, a culture of support and openness. We want to improve that sense of community and energy.” How do you do that in a program where a third of the constituents graduate every year? Where the participants are to some degree in competition with each other? Where the old methods are entrenched in generations of tradition?

THE SOLUTION: BOTTOM-UP EMPOWERMENT

Hagan’s approach had several key components: Empowering the motivated. Hagan realized that not everyone in a fluid organization will see the value of investing in a difficult change process. The key to the improvement process in the Cardiology Training Program was to center on empowering the Fellows to build the program and the culture they wanted. The strategy was to start where intrinsic motivation was strongest and look to create a tipping point with the others. “You need some people who are going to be your champions,” said Hagan, “who see the vision or have the ideas.” You hand them the keys to the car. The “car” you put them in should give them a rhythm for reflection and dialogue about the culture and should show them how to translate their ideas into action. Setting the expectation that change is achievable. In an entrenched culture, it’s important for leaders to demonstrate humility and curiosity, creating a space for dialogue, and giving people hope. Some won’t believe it until they see it, but others will catch the vision and begin to contribute. Ensuring immediate initial results, even if they’re small. “If you say you’re going to do something and then a couple of months later nothing has changed, you’re done!” cautioned Hagan. “And luckily, the Fellows were able to really make some rapid improvements in a very short period of time.

Basically, Fellows came up with ideas and said, ‘I want to do this,’ and off they went.” Building a foundation for longer-range development. Over time, deeper-rooted issues will emerge. Early successes set the stage for tackling them. “We set a vision,” Hagan said. “We want to be the ideal training program. We want to empower and leverage our Fellows to be builders. We want to develop a strong culture, a culture of ideas, a culture of support and openness. We want to improve that sense of community and energy.” Overcoming in-house competition. It’s important to build a team spirit, as well as to promote opportunities for individuals to capitalize personally on contributions they make that benefit the whole group. People “buy in” for both selfless and selfish reasons that are rarely mutually exclusive. Capitalize on both. Using the rapid employee life cycle to energize the culture work. Embrace the reality of an organization’s fluidity as an opportunity to define many touch-points to the culture work: to promote the vision and to pass the baton from one “generation” of constituents to the next. Tracking Outcomes. It’s essential to have measurable goals and outcomes. Hagan used the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) annual, national survey of Fellows nationwide, combined with annual use of the Denison Organizational Culture Survey (DOCS) with his own Fellows, to track their satisfaction before and during the ongoing culture change project.

THE RESULTS: EDUCATIONAL TRANSFORMATION

By all accounts, the Cardiology Training Program’s culture project is an ongoing success. Hagan handed the reins to four of his Fellows. Prashanth Katrapati, M.D., was the Chief Fellow when the culture change project began. Matthew Konerman, M.D., was the Chief Fellow the following year. Dan Alyesh, M.D. and Craig Alpert, M.D., were co-Chief Fellows the third academic year. All have now graduated, and all but Dr. Alpert were available for interviews, from which the quotes below are drawn.

Dr. Konerman: In a way, the culture work was a sort of crash course in leadership. One of the basics I’ve taken with me into my new role is the importance of getting organized and clarifying objectives with the teams I’m leading. With my nursing team, I’m paying more attention to how I can adjust my style and expectations based on their needs. Empowering the motivated. Hagan found motivated leaders who could motivate others. For Dr. Katrapati, the ability to shape the training process was key. “At the end of the day, the reason that you’re there is to learn and set yourself up for the future. And the fact that we were able to now tailor our own education to our needs, and be able to speak up about it when it wasn’t set up to our needs, was the biggest action item that I think helped overall.” For Dr. Alyesh, this was a lesson in the importance of empowerment: “Listen to those who are in the trenches and do the hard work. . . . Harness their creative energy toward making an improvement in what they care about, and trust that they’ll do a good job.” Setting the expectation that change is achievable. “The number one thing was that everybody realized that they could make a change,” said Dr. Katrapati, “and I don’t think that was the case before we started this process. The guy at the bottom now has a voice, and that voice is heard. And the guys at the top are more open to the idea that change can happen.” Alyesh concurred. “There is a collective belief in the ability and the need to get better. There is a tremendous amount of pride–there was always pride–but that has escalated.”

Ensuring immediate initial results, even if they’re small. From Dr. Katrapati’s perspective, starting small was a key to success. “What we did well at the very beginning was to identify a few things that were specific and also easy to achieve. We didn’t go for the home runs in the beginning, and I think that helped a lot.” Some examples: the Fellows hosted a barbecue with faculty and alumni. They made more time for socializing with their peers. And they had the Program buy fleeces emblazoned with the program logo for each Fellow as a symbol of getting more intentional about their brand. The first wins were small but important. Building a foundation for longer-range development. As time went on, the Fellows identified curriculum needs and explored new avenues for collaboration. They invited outside speakers to present on the topic of leadership. They started a process to redesign their work space to allow for greater peer collaboration. They engaged the faculty within the division in a similar process of culture introspection and dialogue. They even developed substantive new programs within the program. “One example of a program that was very successful,” said Dr. Konerman, “was the creation of a clinician education pathway which addressed a core need in our training. We proposed the idea to the Graduate Medical Education (GME) at the University and got it approved . . . We had trainees across the hospital apply, and we selected 25 to participate in the initial program. The program has scaled to other departments.”

Dr. Alyesh proposed and successfully secured funding to create the first annual Value Innovation Challenge, a program designed to solicit improvement ideas from the entire UM Cardiovascular Center community, including the patients and families served by the center. The winning idea(s) will be turned into action. Overcoming in-house competition. “One thing that the Program Director does,” says Dr. Alyesh, “is get us to think about our Fellowship as a locker room, a team–check our egos at the door–and not see each other as the competition.” Konerman noted that there were also opportunities to contribute to the group in ways that had personal benefits, too—a win/win. “We were able to promote ourselves through the culture work. We learned that we could be creative and start projects that would benefit us personally. Some of the projects were turned into papers and benefitted peoples’ academic résumés. But people also really got behind the projects that supported quality and patient care. That stuff carries beyond the individual.” As one example, Dr. Hagan and the Fellows wrote a paper summarizing their culture work, “Better culture, better physicians: Empowering Fellows to measure and improve training program culture,” which was accepted for oral presentation at the 2016 International Conference on Residency Education (September 30th ) in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Using the rapid employee life cycle to energize the culture work. The Program made culture a core component of their new Fellow recruiting process. And as senior Fellows took new jobs, they passed on their “champion” role to more junior Fellows so that the process could repeat

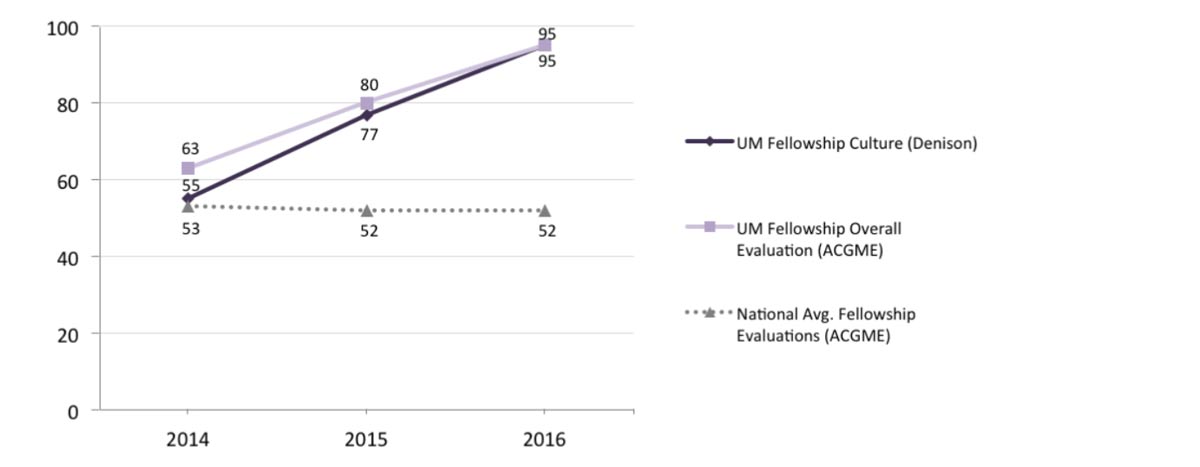

Tracking Results. Survey data tracked over the three years since this work validate the progress, showing steady improvement in Fellows’ perceptions of the culture and their satisfaction with the program. The percentage of Fellows whose rating of the program is “very positive,” the highest rating category on the 5-point scale, was up nearly 20 points to 80% overall, whereas the national average is 52%. In addition, every year, the Fellows are asked another question (anonymously): What percent of your personal potential do you feel that you are achieving in the program? The Fellows’ response to this question also improved, rising by 10 points, to 80% overall. As Dr. Katrapati put it, ”My biggest takeaway is that there is a way to assess culture, and that you can actually change it. But you have to identify what is wrong and where the problem is in order to impact change.” Beyond data, anecdotal evidence is important, and the news is good here, too: faculty members across the division have asked “What’s different with the Cardiology Fellows?!”

Top-Down or Bottom-Up?

Program Director Hagan was insistent on a bottom-up, Fellows-centric approach to culture change, giving them both the mandate to identify the changes needed and the reins to drive the creation of solutions. That said, it’s important to point out that his leadership was crucial to the program’s success. Dan Alyesh put it this way: “We believed change was possible pretty quickly because we had leadership and we had the Program Director who believed in the need to change, to improve.” Dr. Konerman concurred: “… I came to really believe in the idea that I could create something. It was very important to hear the Program Director reinforcing that message and acknowledging some of the ways the Fellowship could be improved.” Konerman became a conduit for the same message. “When I became the Chief Fellow, I tried to do my part to empower the other Fellows in the same way the Program Director had done.” Finally, Konerman noted the importance of engaging the Faculty in order to ensure continued success. “I think this is the ceiling of our improvement. The bottom-up efforts of the Fellows can only go so far, and then you really need the support and active engagement of the Faculty and the Division.”

What can we learn from universities?

The Cardiology Fellowship Training Program at the University of Michigan provides a fascinating example of the meaning and management of culture in an organization whose members are always on the move. What they have learned about how to create and sustain their program’s culture holds strong relevance for many organizations today, including some (like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb) who are defining new organizational forms, as well as to many others who are grappling with a high-churn millennial workforce.

Find the people who have the energy, and hand them the keys to the car. The “car” you put them in should give them a rhythm for reflection and dialogue about the culture and should show them how to translate their ideas into action.

Figure 1. Improved Culture Translates to Improved Training Experience

Note: The Fellows’ ratings of the program culture are percentile scores in comparison to Denison’s global normative database. On an annual basis, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) conducts surveys of all accredited medical Fellowship programs in the U.S. The numbers shown above from the ACGME survey represent the percentage of Fellows who evaluated their overall experience in the University of Michigan (UM) Cardiology Fellowship Program as “Very Positive”, i.e., a 5 on a 5-point scale. In comparison, the national average according to the ACGME has been steady at 52%. For more details on ACGME, please visit: https://www.acgme.org/

References

Footnote 1: “Most remarkably, the number of Americans using these alternate work arrangements rose 9.4 million from 2005 to 2015.” Check out Neil Irwin’s article in TheUpshot: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/31/upshot/contractors-and-temps-accounted-for-all-of-the-growth-in-employment-in-the last-decade.html?mwrsm=Email&_r=0 Comments by Dr. Peter Hagan are excerpted from his 2016 invited presentation at the Denison Best Practices Forum. Comments by former Cardiology Fellows Dr. Katrapati, Konerman, and Alyesh are taken from a group interview conducted by Dr. Levi Nieminen. For more of the fascinating details of the culture transformation project at the University of Michigan Cardiology Fellows Training Program, see the full text of Dr. Levi Nieminen’s two articles on which this case study is based:

Connect with Insights from Denison

If you’d like to be kept up to date when we release a new TRANSFORM article or important piece of research, we can notify you so you have immediate access. Yes, please let me know.