Trust and Leadership

By Karl-Heinz Oehler, Partner and Managing Director

Denison Consulting Europe

Denison Consulting Europe

Leadership is a collective act

As the world of work changes, to use a popular phrase, we see a proliferation of articles and blogs addressing leadership effectiveness, offering suggestions of what successful leaders (should) do. Whilst almost all of those suggestions make sense, they appear to limit and reduce leadership to the acts of an individual. Yet, as I have worked with hundreds of leaders across my career, I have come to see that leadership is a collective act at all levels of the organisation.

One role of leadership is to unite employees to “take the lid off” and to create an environment which enables them to apply their energy and ambitions to achieve both personal and professional growth. This cannot happen without an environment of trust. A critical goal of leadership, therefore, and especially of collective leadership, is to build trust across the organisation. The focus on building a “high performance culture” is increasing at many companies, but the need for building trust through collective leadership is equally important.

The shift in workplace culture and values

Like many others, I have observed a strong shift in workplace culture and values in recent years. The emerging generations entering the work market appear to place much more importance on meaning and purpose in the jobs they perform. In addition, independence and entrepreneurship, inclusion and diversity, workplace flexibility, quality of life, digitalization and mobility are fast growing expectations among this population. Organisations will have to shift from being control-centric to becoming facilitators of networks and platforms connecting employees in their efforts to contribute and perform. The consequence is a different organisational ecosystem in which relatively rigid value chains and value creation processes change fundamentally, becoming much more fluid and adaptive.

Such evolutions require a different style of leadership. Of course, individual leadership can still shape the culture of an organisation, but collective leadership, building trust within an ever-changing work environment, will be much more powerful and create much more impact than any individual leader can achieve alone. Consistency in leadership is of utmost importance when building trust, because leaders operate at all levels and trust enables co-ordination without coercion or competition. (Gray and ’t Hart, Public Policy Disasters in Western Europe; Collins and Thompson, Trust Unwrapped)

But why is trust so critically important?

Trust is something we need before we commit ourselves, and it enables commitments to be undertaken in high-risk situations. Trust provides a feeling of comfort and courage, whereas lack of trust generates a feeling of insecurity. We tend to quickly make assumptions about whether or not an individual or organisation is trustworthy and seek evidence that confirms those assumptions to be true, often ignoring other data that might challenge them. Organisations need to decide what trust means to them and what areas of trust they will insist on. For example, if integrity and respect are key values for company XYZ, would XYZ fire their most successful sales person if he was a bully, consistently acting disrespectfully toward others? Not acting on values undermines trust in the organization.

Creating an environment conducive to building trust is easier said than done, as many examples in industry and social life demonstrate so painfully (Volkswagen’s scandal of falsifying emissions tracking data—implicitly or explicitly accepted by leadership—and PostBus Switzerland’s use of irregular accounting practices whereby leadership attempted to conceal the diversion of profits from its subsidized regional transport business into other profit-making areas of the business—are just two recent instances.) So, trust and leadership are intrinsically linked. If we don’t trust in leadership, we simply will not commit ourselves, and this is not solely an ethical issue isolated from productivity. As Stephen Covey argues in his books The Speed of Trust and Smart Trust, trust is not a soft, social virtue, it’s truly a hard, economic driver for every organisation.

Building credibility and trust

Let’s look at three factors that contribute to building solid credibility and trust: unified commitment, transparency of intent, and affection and respect.

Building trust through unified commitment

Imagine a leadership meeting attended by key stakeholders assembled to decide a critical shift in the strategic direction of a firm. The employees know this meeting will be taking place and are anxious to learn what the decision might be, as it may have significant consequences for the larger organisation and for themselves. After a long deliberation, the leaders return to their respective teams to communicate the outcome. One leader communicates the decision without expressing any judgment. Another leader communicates the decision, but adds a comment such as, “Well, that’s the party line, but I am not really in agreement with the decision that was made.” I have far too often observed situations in which leaders (at all levels, by the way) made statements along those lines. It typically happens when the leader believes that the decision may be perceived as unpopular and will result in a challenging discussion with the team.

The intent of the statement, then, is to “soften” the impact by giving the impression of being on the side of the team.

Unfortunately, communicating a decision in this way most likely will not only undermine the credibility of the leadership team, but also ultimately reduce the level of trust in that particular leader. “But there was no evil intent behind the leader’s communicating the decision to the team this way,” one might say. “It’s only human. ” Yes, maybe. But most people want transparency, and the truth will probably come out one way or another. If that happens, the exposed leader will feel pressure to justify why he communicated the decision this way, and this justification, in turn, will most likely create skepticism, undermining trust even more.

My first point, then, is this: A critical trait required for collective leadership to build trust is unified commitment.

What is “unified commitment”? Simply put, it means that team orientation is more important than self-orientation. Any individual team member foregoes personal motivations, intentions, and objectives in favor of the goals and common interests of the team. It doesn’t matter how tense and controversial the leadership meeting might have been, once the leadership team leaves the room, it speaks with a unified voice. Behaving along these lines requires character, as it demands a strong sense of loyalty and dedication to the team.

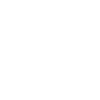

Now, please don’t get me wrong: I am not talking about blind followership and political correctness. I am speaking about creating trust through authentic behaviour. Leadership team disagreements and their consequences have to be discussed and handled, but within the leadership team, not in the public space. Self-orientation is the enemy of trust, as we are reminded by Maister, Green & Galford in The Trusted Advisor:

Building trust through transparency about intent

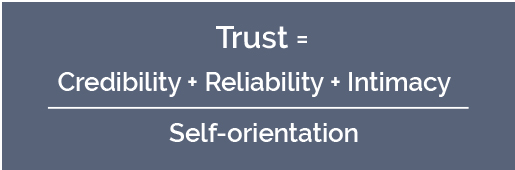

I want to come back to intent. Take a look at

Figure 1. The inner circle shows what is core for all of us: we all have beliefs, convictions, and fears that motivate us. They are part of us and make us who we are, but we hardly speak about them. They are at the source of our intentions, represented by the second circle. Intentions can be described as the personal agenda we establish to create a personal and collective impact. Here again, we don’t easily speak about our intentions. Instead, we demonstrate them through our behaviour, the third circle. Unfortunately, behaviour is often the only visible element. Observers often don’t know what is behind the behaviour, so they make assumptions, most likely inaccurate ones.

Trust cannot be established without openness about intentions. It’s important to declare what one is all about, how one prefers to operate, and what one expects to achieve. To be effective, declared intentions must be genuine and must be rooted in a clearly defined mutual benefit.

One important element of transparency regarding intent is clarity about outcomes expected from relationships on a personal, team, and organisational level. There needs to be alignment between personal and organisational values of all leaders at all levels across the organisation.

Here again, team orientation trumps self-orientation in order to achieve the best possible outcome for the benefit of the entire organisation.

One major contributing factor to building trust is consistency. This has two parts: consistency in values (“walking the talk”) and consistency in results (measurable goals achieved). This consistency leads to creditability, which engenders trust. Consistency in delivering promised results (which, by the way, is a collective leadership challenge) will continuously enhance overall confidence in the leaders’ ability to contribute.

Declaring intentions becomes a powerful building block for credibility, even though our behaviours, admittedly, don’t always quite do them justice! In an open environment, when behavior doesn’t appear to match stated intentions, conversations can be had to acknowledge the disparity and correct it or to explain what additional factors led to actions that were different from the expected ones.

In his research for The Speed of Trust, Stephen Covey found that declaring intent reduces resistance while enhancing commitment—especially in situations where there are new leaders in charge, massive change is under way, or in which employees assume that leaders’ motives are mixed.

Building trust through affection and respect

In an environment of trust, challenges appear to be more easily addressed and resolved than in a low trust environment. This is often attributed to the fact that, under conditions of high trust, problem solving is much more creative. Why? Because when trust is high, relationships are much more transparent and open. Judgment is suspended, personal risk is lowered, and listening to each other prevails, leading to much more productive exchanges. Offering “out-of-the-box” ideas that can lead to unusual problem-solving approaches is encouraged.

When trust exists, respect and affection are the foundational factors of interaction. This “common sense” observation is not always so common. On the contrary, it is absolutely amazing how often these traits are neglected or ignored, especially in male-dominated environments. The meaning of affection is so many times misunderstood and, therefore, seldom tended to with purpose. But what does “affection” mean in this context? “Does it mean hugging?” one leader asked me in horror. No. It means the genuine desire to be part of and to work with an individual, a team, or an organisation.

But it’s not enough to say you respect people’s feedback or contributions. Respect and affection must be demonstrated consistently. In a team in which two or more members dislike each other, chances are that the entire team will suffer from those relationships and initial trust will slowly fade. If this happens, these interpersonal relationships interfere with and distort the team’s perceptions of the issues it is tasked with handling. Worse, the team’s energy and creativity are diverted from finding a practical solution to those issues, and the problem team members will most likely use the team context as an instrument to minimize their vulnerability.

Affection and respect go hand in hand. Wanting to be part of a team, to drive collective achievement for the greater good of the company, appreciating diversity of thought and diversity in the team set-up, recognizing and acknowledging the knowledge and wisdom of others—these are all factors that engender respect and affection. And it is this environment which role-models the creation of trust, not as an exceptional state, but as the normal way to work together.

Trust is a business driver

The advocacy group Trust Across America has found that the most trustworthy companies have outperformed the S&P 500. Furthermore, a 2015 study by Interaction Associates shows that high trust companies “are more than 2½ times more likely to be high performing revenue organisations” than low trust companies. In other words, trust is a business driver.

In their book Trust Unwrapped, Dan Collins and David Thomson point out that trust reduces stress! They claim that, when people fail to trust colleagues, they have a tendency to:

- Attend unnecessary meetings in case people talk behind their back

- Request to be copied on unnecessary emails

- Fail to delegate

- Experience anxiety that they may be passed over for promotion

- Conclude that, when things don’t go their way, a plot exists against them

- Don’t ask for help as it may be perceived as a sign of weakness

Does this sound familiar? Then it’s probably time for your organisation to take a hard look at how you can consciously work to build trust into your relationships and operations. In fact, it’s a prerequisite to high performance! It’s likely not a quick-fix. And it’s not a solo job. Yes, a single leader can build trust, but there will be important limitations unless all other leaders share the same approach. Collective leadership is crucial to building trust across the organisation: collective leadership that is dedicated to unified commitment, transparency of intent, and affection and respect.

Connect with Insights from Denison

If you’d like to be kept up to date when we release a new TRANSFORM article or important piece of research, we can notify you so you have immediate access. Yes, please let me know.

[gravityform id=”2″ title=”false” description=”true”]